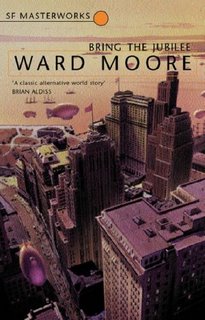

#11: Bring the Jubilee (1953) by Ward Moore

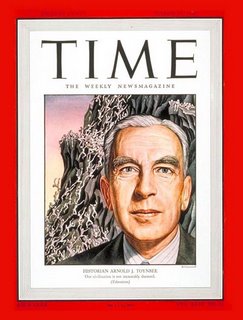

“The historian is always conscious of destiny. The participants rarely--or mistakenly.”

One of the staples of the sf literary diet is the alternative history/alternative reality subgenre. Really, this type of storytelling has been around since the first person thought “what if blumpity blump happened instead of…,” which I imagine was a long time ago (what if Ung crushed Grok’s skull with a rock instead of Bron’s). In the modern age, there are two main events sf writers have tended to ask the what if question of--World War II and the Civil War. I would guess this is because both are often perceived to have been “won” by the “right” side. So wouldn’t it be scary if the bad guys came out on top for once. One of the defining novels of this subgenre is…wait for it…that’s right…Ward Moore’s Bring the Jubilee.

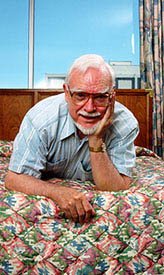

Joseph Ward Moore (1903-1978) was certainly not prolific, but because of Bring the Jubilee and his earlier novel Greener Than You Think, he’ll always have a place of honor in the field. BTJ is the story of Hodge Backmaker, a child of the 20s living in a world where the Confederacy won “The War of Southron Independence.” The United States is a backwater collection of 26 states barely surviving, while the Confederacy encompasses not only the southern part of our US, but also much of Central and South America. So while New York is a city of 1 million in the 1940s, with folks still driving horses and Brooklyn acting as a neighboring city, the real centers of industry and growth are St. Louis (finally we come out on top of Chicago!!!), Washington-Baltimore, and Leesburg (formerly known as Mexico City). The United States has also driven out all black folk, seen large anti-Asian (murdering) campaigns, and exists in a state in which most of its inhabitants live indentured to the few landed families left. The Confederacy, on the other hand, abolished slavery and has an open immigration policy. Along with Britain, which also rules British America (Canada), and the German Empire, which grew unfettered during the Emperor’s War (WWI), the Confederacy is a world superpower.

Now Hodge is a historian by profession, and since the great eastern schools in the United States are just hollow shells of learning, he joins an interesting commune in Pennsylvania known as Haggershaven. Haggershaven is an alternative to the university system. Scholars, researchers, intellectuals live together on a farm, sharing both chores and intellectual pursuits. Among these folks is the inventor of a time machine. What better device is there for a historian than a time machine? Well, the problem is…

I’m glad David Pringle made me sit down with this one; it would have sat on my “to read” shelf forever if not. And that would have been a shame. The novel is fascinating. Moore’s characters are either actors or spectators. Hodge is the latter. At times this is a saving attribute, other times not so much. While on the one hand he befriends an intellectual from Haiti named Enfandin, he also spends his early adulthood loyally working for a member of the Grand Army--an organization that plays a similar role in the alternate US that the Ku Klux Klan played in the real South after Reconstruction. And there are other fascinating aspects about this world: the 40s and 50s are almost like the 19th Century of our world, only with gadgets (almost steampunkish if you ask me); familiar figures take on new roles (Henry Adams is the author of Causes of American Decline and Decay); Freud seems not to have developed psychiatry, rather a fellow at Haggershaven is doing that work; and there’s a damn time machine, people!