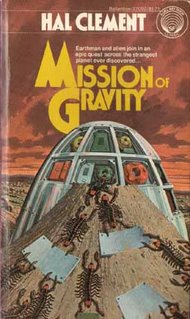

#15: Mission of Gravity (1954) by Hal Clement

“I want to know why a fire glows, and why flame dust kills. I want my children or theirs, if I ever have any, to know what makes that radio work, and your tank, and some day this rocket. I want to know much--more than I can learn, no doubt.”

David Pringle once said that Hal Clement (Harry Clement Stubbs, 1922-2003) wrote as if he had a slide ruler next to the typewriter. Clement was one of the fathers of a subgenre in science fiction known as “hard sf,” and Mission of Gravity is usually considered one of the first novels of this type. Like any genre, subgenre, or the like, the meaning of what hard sf is creates debate. In my mind, sf is literature that has ideas for protagonists, and hard sf is sf storytelling where accurate scientific ideas play those roles. There’s no question in my mind that MG is a hard sf novel.

Clement is a world builder. His creation in MG is a large planet called Mesklin. Mesklin is shaped like a very wide but quite short top. And like a top, it spins quickly. A Mesklin day lasts about 18 minutes. The shape of the planet and the speed of its rotation also create variable gravity on the planet. At the equator, Mesklin’s gravity is about three times that of earth. At the poles, somewhere around 700 times. Before the novel begins, an important human research vessel crashes near one of the poles and human Charles Lackland has made contact and developed a limited relationship with a Mesklinite trader ship captain named Barlennan. Mesklinites look much like centipedes. They’re also instilled with a deep fear of falling (mere inches at the poles could be fatal).

Most of the novel follows the adventures of the Mesklinite crew as they journey from the “Rim” (equator) to the pole, in order to retrieve the information gathered by and stored in the earth research vessel. They’re guided, at first in person, later through instant communication, by Lackland. Barlennan and Lackland respect and trust each other, and because of it, the Mesklinites, who are rather primitive in some ways, ask for more and more human knowledge about the sciences.

Though he was also a painter (under the name “George Richard”), Clement was trained in science, and he spent most of his life as a high-school science teacher. Perhaps this explains why his dialogue and character development are wooden. Really, the narrative seems often to exist solely to give structure to Clement’s scientific points. But that’s not to say the novel isn’t enjoyable. In fact, the journey of these strange centipedes is oddly compelling, and I think Joseph Campbell would have been proud of Clement’s presentation of the hero’s journey. But as Peter Nicholls once said, the reader is introduced to these fantastic and believable creatures from another world, and then they open their mouths and “sound exactly like Calvin Coolidge.” Fascinating Calvin Coolidges though I must add.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home